Lessons learned from Rubbish Science Sessions in a Sierra Leone Rural School

Sierra Leone is a beautiful country in West Africa, home to some of the genuinely friendliest and nicest people on the planet.

It has beautiful beaches, but tourism is very underdeveloped. The country has a long history of being a hub for slavery. The capital, Freetown, was founded as a home for repatriated slaves in 1787. A brutal 11-year civil war ended in 2002 but left a legacy of child soldiers and orphans. A UN report in 2006 counted over 300 000 orphans out of a population of only about 6 million. A new government in 2018 pledged free education for all and has implemented this. A huge undertaking in a country where about 30% of school-age children don’t attend school. Rubbish Science is particularly appropriate as there is a lot of rubbish and very little recycling is done.

This trip was organised by the charity Operation Orphan for which Rubbish Science focusses on ‘Keep a Child Learning ‘

My class smiled slightly nervously at the start of three days of intensive Rubbish Science. How much impact could we make to their thinking? Can you really significantly develop scientific literacy in such a short period of time?

The Ebola virus epidemic that ended in 2016 had devastated the area and left many of the class without parents and family. There had been a huge disruption to their lives and also obviously their education. Several of the students were much older but had been held back as they hadn’t reached the required level to move up.

The Rubbish Science curriculum aims to condense science to its core components and to develop scientific literacy. The ability to solve problems in a systematised and creative way. This is often at odds with the passive way they learn in schools.

An unforeseen problem in Sierra Leone was in sourcing the rubbish required. They have an economics of scale. Things are bought in small quantities when needed. If you are hungry you buy a handful of peanuts, not a large packet to store the rest. Water is sold in plastic bags so plastic bottles are quite rare in the area our school was. Fizzy drinks are sold in returnable glass bottles – but none of my students had ever tasted one. There were no tin cans, nor shiny crisp packets as these were items not purchased by a relatively cash-free society. We should never assume all items of rubbish are available, some things are a luxury.

Claim – Evidence to support the claim – Confidence in the claim

As a Rubbish Scientist we make or look at a claim (a hypothesis) that may be supported with some evidence. We then state our degree of confidence in that claim.

We then look for evidence that may or may not support that claim to increase, or decrease the level of confidence. It is important to understand we are not trying to prove that claim as this may lead to bias.

The class were trained to shout “where is the evidence” whenever I made a claim to put this in practice. I made a claim that I could run faster than one of the students “where is the evidence” the class shouted. We went outside and I challenged the students to a race, however, I made my challenger run through some bushes to the finish line and I had a clear run. I won and said “Here is the evidence!” the class were not impressed “That’s not evidence!” they said.

We also used Virtuali-Tee that had them fascinated, but also a little scared by it. I claimed I could see inside their bodies and the evidence suggested I could, then we held it up without a body and discovered I couldn’t. You can buy a Virtuali-Tee here and if you use the code RUBBISHSCIENCE you get 20% off

We ran again this time both on the easy surface. This time I started ahead of him. I won again. The class were even less impressed “That’s not evidence ” they shouted.

On the final run, we ran a fair race and my challenger won. “Is this evidence?” I asked the class. They were now happy. We discussed how we could make the evidence stronger and how could we have more confidence in the claim. “Repeat it many times,” they said and we were well on the way to creating scientists.

On failure and how scientists never fail (If they survive!)

Back in the classroom, we tried the finger and coordination exercises that nearly all the students failed at least one.

The focus was on to redefine failure as a learning experience and failure shows us where our limits are. Failure is not the end it is the beginning of the journey as long as we learn.

We did the helium straws activity ( This will be in the booklet when published) to improve communication and problem-solving skills and we celebrated failure.

Armed with this new mindset be tackled the newspaper tower challenge using the planning sheet

What do you know about stability? Why do things fall over?

One of the problems facing the students this particular challenge was that in their rural area they may never have seen tall towers or buildings. Fortunately, I had noticed some pylons in the distance. We went outside and I asked what’s the tallest thing they could see. They all pointed to the trees that were close by. I pointed to the pylons and asked: “What about those?” They looked uncertain: “How many of you have been up to that pylon?” I asked: none of them had. We have to be careful about making assumptions!

We talked about centre of mass and modelled it with their bodies looking at stable and unstable shapes to get the idea that by widening the base and lowering the centre of mass we can increase stability.

We prototyped their ideas for the newspaper tower. Many of the students made boats or origami structures rather than trying to attempt the task. They showed me their handiwork proudly. I complimented them on their origami skills pointed out this wasn’t going to help the task. We looked at each other’s models to try and decide which might be the most effective solution. The final models when much better but what was clear was that some of the students would struggle to think on their own without direction. It seemed that under pressure to think, they produced something that they knew as opposed to tackling the new problem. They were very eager for praise and to get the answer correct.

As we went through the other tasks it became clear the many were developing good strategies. They were learning to try things out first before they asked and were developing a degree of independence. They seemed not so frightened of failure. I was particularly impressed with the girls’ attitude when asking for volunteers as many girls as boys volunteered. In terms of gender equality, the classroom seemed quite an equitable place. I did a count of boys vs girls talk and it was roughly comparable. If you want a tool then try this one Are men talking too much?

Fishing Lines from Plastic bags

Students were terrific at this really exploring the best way of making the line. At first they thought the challenge of making at least one metre long would be impossible, but one by one they managed it

Plastic Bag Balls

A newspaper core wrapped in plastic bags and tied with string, plastic bag balls are easy to make. But how can you make the bounciest one? and how will you test it? A lot of modelling went before this to see whether students could carry out their own investigations without help. They were not there yet. Balls were dropped from different heights at different times and they needed directing in order to make a valid experiment

Hydroponics

One of the problems with a one-off session is that seeds take such a long time to grow that we can’t see the results. Students chose their seeds and planted them and hopefully we can get some results later.

For the bottle gardens we purchased some pepper seedlings and used bigger bottles – that were hard to source (Eventually found from the expats – one of my ex-students is working out in Sierra Leone ) Students were given access to two types of fertiliser and given a free choice what to do to see if they would create groups comparing the effect of fertiliser strength. They didn’t, instead, they put as much fertiliser as possible. Their thinking seemed to be – “Fertiliser is food for plants so the more you give them the better your plants will grow”. We were still a way off getting them to think like scientists.

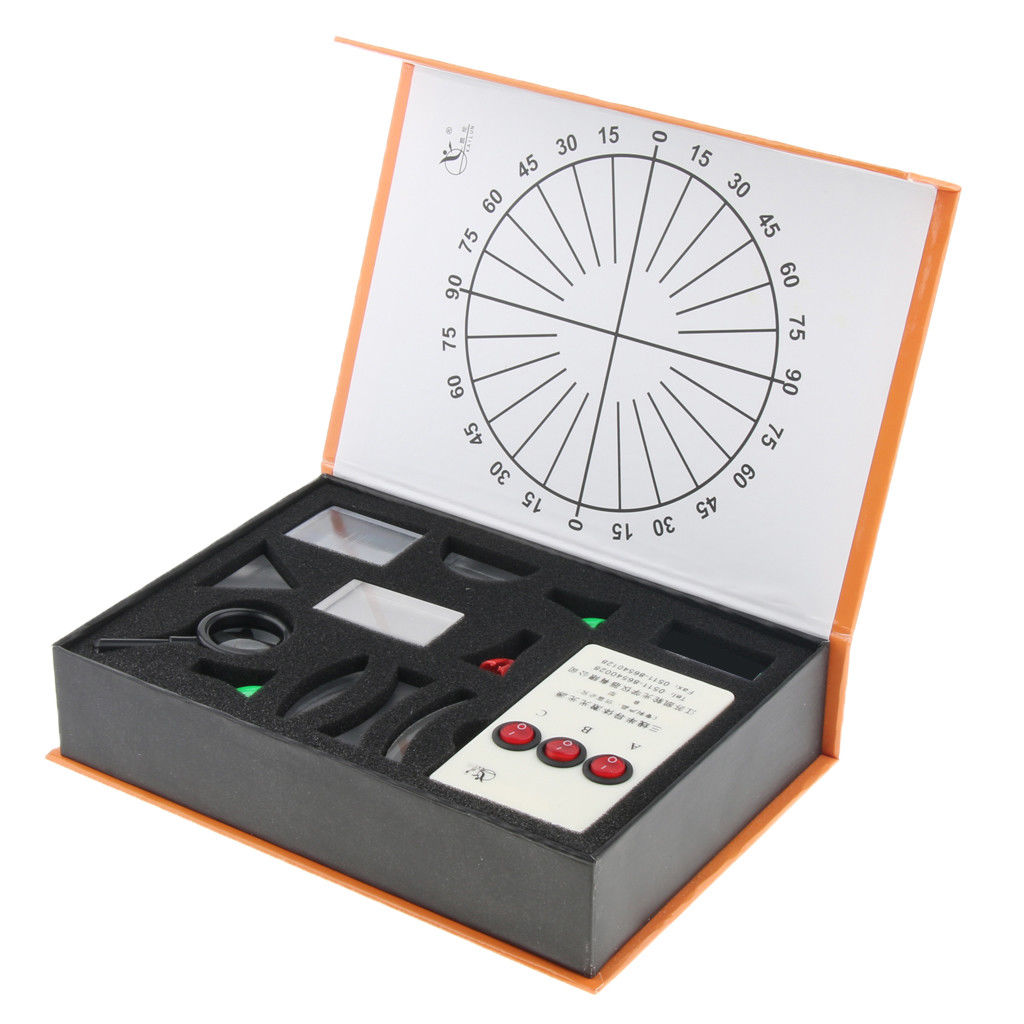

I had bought a cheap optics laser kit that was perfect and the students picked up the concepts quickly by showing with their arms whether there would be convergence, divergence or straight lines. They were happy with this much more conventional task and were good at it despite only ever having seen ray diagrams drawn on the board.

The water rocket although not really a Rubbish Science activity. provided lots of excitement and the learning points about forces were taken on board. Useful questions were:

Why does the rocket take off?

What might happen if …… The bottle was empty/full/a larger/smaller bottle used?

Why does the bottle come back to Earth?

Under what conditions might it leave the Earths gravitational field? and why is this not likely to happen for a water bottle?

Electrical circuits were done with button cells, LEDs and copper tape. There was some very impressive experimentation going on. There was definitely a change in attitude with less helplessness and more independence and collaboration. The creation of series and parallel circuits was very heartening.

We did the Insulated flasks as a precursor to the solar stills. Using the infra-red camera to see the greatest areas of loss. They did well at this. The ‘winning designs’ (remember the winner is the person who has learned the most) using the silvered insides of sweet packets as reflectors directly against the plastic bottle and cardboard as insulation. It was the effective use of lids that made the difference reducing heat loss by convection.

We used what was learned from the Insulated Flask activity to create Solar stills. We had discussions about the factors that might affect heat gain. The infra-red thermometer and infra-red camera (A Flir One used on a smartphone) both indicated that the surface temperature of black skin was around 3C greater than my paler skin. Absorption and reradiation is a difficult concept. The Solar stills were set up and left overnight to get better results, however in the morning we discovered they had been thrown away – The problem of using rubbish to solve problems is that it looks like rubbish!

The tin roof of the classroom showed a reading of 65C using the Infra-Red thermometer and there was little airflow. It would be interesting to explore how to cool down the classrooms – Painting the roof white? Plastic bottles as insulation? – Is this a potential fire hazard? It was so hot in the classrooms that this should be seen as a priority for future investigations.

I missed them for part of the afternoon as I had a meeting with the Sierra Leone Education Minister with a view to putting on a conference in August. Follow this blog for more information.

We finished with the sex and milk activity, but I hadn’t had time to check the strength of the starch and so despite the big build up it didn’t work. I was disappointed and said oh no I’ve failed. A delightful response was them shouting ‘fail is the first attempt in learning!’ Job done !

I managed to do some Teacher Training using Rubbish Science ideas and the excellent Marvin and Milo activities published by the Institute of Physics with more materials here

In Summary

The intensive 3 days with a single group is what changed their way of thinking. At the end of the first day, I was feeling frustrated that I hadn’t moved them on. At the end of the second day, I was a bit hopeful. At the end of the third day, I was buzzing and left with a tear in my eye. I was so proud of those students they had challenged themselves and pushed their boundaries.

Single lessons are likely to be interesting, or possibly frightening to some as it takes them out of their comfort zone for only a short time. If we want lasting change immersion is probably the way forward. My students were on the cusp of Secondary though many had their education disrupted due to Ebola so were much older. I think younger students may have fewer barriers and be more open to exploration than their older peers, but we need more evidence to find the optimum age and this is likely to vary depending on culture and educational experiences.